Editor’s note: This article is part one of a two-part recap of the Instructional Course Lecture titled “When the Physician Becomes the Patient,” from the AAOS 2023 Annual Meeting. Part two, on how employers can support physicians facing medical challenges.

In introducing the Instructional Course Lecture titled “When the Physician Becomes the Patient,” at the AAOS 2023 Annual Meeting, moderator Miho J. Tanaka, MD, PhD, FAAOS, observed that for the physician facing serious illness, “The difficulty is that in our field we value self-reliance, independence, and self-sacrifice.” Contrary to the facetious observation that “the best doctors have few needs, make no mistakes, and are never ill,” she said, “Physicians are just as vulnerable as the general population, but we just don’t think that it can happen to us.”

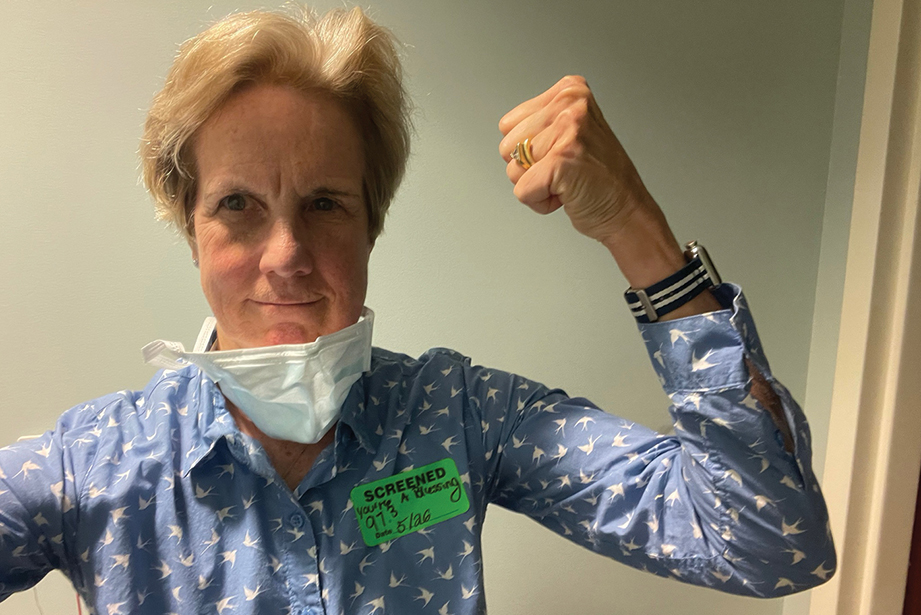

The session offered stories and lessons as related by three orthopaedic surgeons—Christopher Bono, MD, FAAOS; Mary Lloyd Ireland, MD, FAAOS; and Milton “Chip” Routt, MD, FAAOS—who had recently faced cancer diagnoses and undergone treatment. At present, all three report no recurrence of disease. In sharing details of their encounters with serious illness, they related their physical and emotional journeys, the unique challenges physicians may face when they become patients—both in caring for themselves and their patients—and the practical considerations that arise when a busy surgeon takes extended time away from practice.

Dr. Bono presented his story of illness and recovery with an emphasis on how employers can respond and assist in a compassionate, positive way (see accompanying article). Dr. Ireland focused her talk on the perspective of the physician-as-patient and on the matters of “work, life, and leadership” that she encountered after a diagnosis of and treatment for breast cancer.

“‘You have cancer.’ You never think it’s going to happen to you, right?” Dr. Ireland, a professor at the University of Kentucky, observed. “As an orthopaedist doing sports medicine, I diagnose, communicate, implement treatment plans, fix—mission accomplished, and back on the field, and I love doing that. But with a cancer diagnosis, it’s much different. There are many unknowns, uncharted courses, missions less possible.”

She said one of her first thoughts upon diagnosis was whom she needed to tell. “You have to share it with your chair, your administrators, family, select friends, peers,” she said, but “I didn’t really share it with anybody in our department—residents, peers, patients. In my sports medicine practice, I was able to call my patients who were scheduled, and I didn’t try to do their cases or have them wait. I picked from my partners who I thought was the best fit [to cover these cases], and the patients were fine with that.”

In terms of attitude, she said, “You need to surround yourself with positive energy, and always create a homecourt advantage, in the OR or in treatment of cancer.”

What she found helpful was talking with others about her diagnosis, treatment, and feelings. Cards, presents, and gifts were comforting, as were walking outside and being in nature. Seeking a “mindset that we’re gaining control” was a general goal, she said. “I think control is what we as surgeons like, mainly in the OR. We make sure we can do the best for our patients in the OR. And I had [control over my] treatment options—which surgeons, which facility, which radiation oncologist.”

Still, Dr. Ireland found, “There are some situations where we don’t have choices or control.” To address that feeling, she sought to take a role in defeating her disease. “Take anticancer action,” she advised. “Reduce inflammation. It’s bad for joints, it’s bad for cancer. Choose the foods that detoxify, and understand the effects of the foods; anticancer diet books were really helpful. Understand your treatment options, meet the oncology team, read articles and books, and discuss treatment with cancer patients and friends.”

One way that she took control of her disease and the course of treatment was in the choice of surgeon and the location for the operation and treatment. Dr. Ireland said that the first surgeon she saw locally proposed scheduling her procedure as soon as possible. She was advised she did not need to see an oncologist prior to surgery, and that she could return to work in 5 days. “Physically I could, but mentally I was a wreck, and I would not do that to my patients,” Dr. Ireland said. “I just knew that wasn’t the right fit for me.”

She decided to travel to Boston, to Brigham and Women’s Hospital, for her surgery. “I took control,” she recalled. With her friends as advocates, she was confident she had made the right decision and felt she had the “homecourt advantage” as she underwent a subtotal mastectomy, “or basically lumpectomy,” and subsequent radiation. For the radiation phase, she returned home, again seeking to exert control by packing a playlist of songs to listen to during treatments in Lexington and journaling about them.

Now, Dr. Ireland continues to undergo follow-up care at 18 months without recurrence. She had a positive mammogram necessitating a biopsy, but it was negative. “I don’t think we ever know we’re cancer-free, but I think we need to make sure we get those scans early. I get them every 6 months.”

Throughout the course of her treatment, Dr. Ireland, a one-time competitive swimmer who was world ranked in the breaststroke in 1973 and 1974, said, “Friends and family members told me I was the strongest person they knew, so this diagnosis and treatment should be no problem for me. But you really don’t think you’re that strong. You lose that swag or that confidence that we as orthopaedists have. I think ‘grit’ is a good word.”

Her experience with cancer has changed her, she said, specifically in having compassion for others with a cancer diagnosis. She has a renewed desire to be a patient advocate, and in her journey, she learned “how little I knew about breast cancer, even as a physician, albeit an orthopaedic surgeon.” Her illness has made her wish to be more humble and kinder, and now, she said, “I love life and live it to its fullest.”

Terry Stanton is the former senior medical writer for AAOS Now.