Editor’s note: This article is part two of a two-part recap on the Instructional Course Lecture titled “When the Physician Becomes the Patient,” from the AAOS 2023 Annual Meeting in Las Vegas. Part one, which discusses the experience of being both a physician and a patient.

At the AAOS 2023 Annual Meeting Instructional Course Lecture titled “When the Physician Becomes the Patient,” Christopher Bono, MD, FAAOS, spine surgeon and executive director of the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital, shared his story of illness and recovery in the context of how the employer should optimally respond when a surgeon gets sick. He framed his presentation within the question: “What are the departmental/employer considerations when a physician or staff member has a medical issue?”

Dr. Bono, who is also director of the Combined Orthopaedic Residency Program at Harvard Medical School, recalled undergoing a CT scan “out of an abundance of caution” after presenting with a cough he could not shake and shortness of breath after walking a block, despite being a half-marathon runner. The scan revealed a “rather large mass sitting in the middle of my chest,” he recalled, which would turn out to be primary B cell lymphoma.

Upon receiving the diagnosis and embarking on a course of chemotherapy, Dr. Bono shared that at such a life-changing moment, his surgeon mentality turned to his practice—how he would cover his patients, how he would maintain an income. What the physician wants to hear in this situation from his employer and partners, he said, is “‘We’ll figure out coverage.’ ‘Don’t worry about salary.’ ‘Be with your family.’ ‘Keep us updated when you can.’”

What the employer should not do is press the affected physician for an immediate plan. The response “shouldn’t be ‘call me as soon as you find out what’s going on,’” according to Dr. Bono. “It’s not like your chair needs to be the first person to know when you get your tissue diagnosis, or what’s your treatment plan?”

Another question that arises for the employer is whom to notify. “When there’s news like this about one of your faculty, one of your employees, you want to tell somebody,” Dr. Bono said. “And that’s not necessarily the right first step. In my situation, I didn’t really have a lot of secrets, but some people want to keep this to themselves or to a certain group of people. You want to be clear—who would you like to know, who would you like to not know?”

Regarding communicating the news with patients, Dr. Bono said, “As physicians, particularly in elective practices, we have patients we’ve known for years. We have patients who are on the schedule, and all of a sudden, you’re gone.”

He added that the written message he composed for his patients was “one of the hardest letters I ever wrote, certainly one of the most emotional ones.” He listed a host of questions that might arise in deciding what information to provide: “Do you want to tell them that you’re sick? Do you want to tell them that you may or may not come back? Do you want to tell them what your diagnosis is? Who’s going to take care of them while you’re out? Do you have partners who are qualified to do what you were planning to do?”

Dr. Bono noted that he has had colleagues in similar situations who had a mindset of “I’m going to get through treatment in 2 or 3 months” and were determined to follow through with scheduled surgeries, as soon as they might be able to. “Of course, that is not in the patient’s best interest; other plans have to be made,” he said.

As he went on leave, Dr. Bono found that loss of income was a concern. “The conversation is very real-world and practical,” he observed. His institution quelled his apprehension by telling him it would freeze his profit and loss (P & L) position. “Even though it’s eat-what-you-kill, they said they would kind of freeze me in time,” he explained. “They said, ‘Let’s figure it out so that you are not accruing a deficit the whole time you might be out of work for treatment or whatever else.’ So I wasn’t having this secondary worry, ‘Well, I’m going to be in deficit now, and I’ll have to work even harder.’ That should not be the first thing on your mind. As the employer, as the supportive department, establish that [protocol], and then check in in a couple of weeks.”

For an employer interacting with an employee who is sidelined by illness, “You want to put the affected person at ease with all these different things. You want to be supportive, but you don’t want to be probing,” Dr. Bono said.

As the patient, Dr. Bono recalled that his primary care physician “told me one of the most important things, which is that you are going to get barraged with texts, phone calls, people wanting to bring you food, people wanting to ask you questions and sit down with you—and you don’t have to do any of it. You don’t need to reply. I did well with that attention; some people don’t.” He advised: “Don’t be afraid to say, listen, this is my time. I’m going to get back to you when I can.”

During his treatment, Dr. Bono said, there was no getting around the paperwork and details required to go on disability. “It becomes reality when you’re filling out that disability form. You have to put your diagnosis there. Cancer. And it has to be done in a certain amount of time. We’ve been on the other side of it as physicians, fighting with insurance companies, getting a CT approved. Here, it’s the same kind of thing; if you don’t get this done in time, you’re not getting a paycheck.” Short-term disability, he noted, is usually for 3 months and is largely an employer issue. Long-term disability “is really the insurance company. Make sure you are guiding your staff member to get all these things done in a timely fashion.”

After the active treatment and recovery phase, the return to work can be a formidable challenge, Dr. Bono said. “The mental health aspect of this really is quite significant,” he acknowledged. “When there’s no longer an active fight, sometimes your mind can take you to some really dark places, and you can be continuously worried if it’s going to come back. There are lots of possible resources for this. It’s good to get it out in the open, and that doesn’t mean that you have to tell everybody on the street that you’re having a tough time dealing with it. But there are employee assistance programs. Ultimately, for me, I ended up seeing a psychiatrist, and it changed my life.”

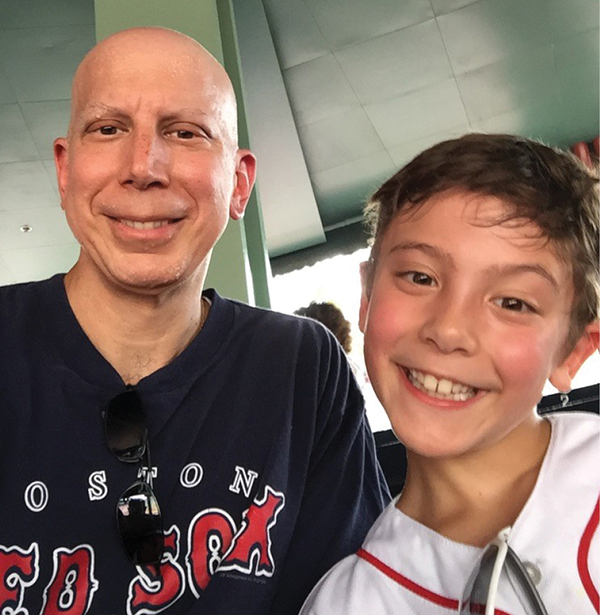

For friends and colleagues visiting a patient with cancer like himself, Dr. Bono had some advice about what to say and what not to say. “Don’t say, ‘Oh, my mother had cancer last year, I know exactly what she’s going through,’” he advised. “That does not work. Your mom having cancer is not the same as you having cancer, especially if your mom was 85 years old. It’s a little different when you’re 45, have three little kids at home, and you have all of these other things that are still on your mind.”

He cautioned against saying things like, “I feel so bad for you.” “We all understand this comes from a place of caring and a place of compassion,” Dr. Bono said, “but it’s not necessarily what we want to hear at the time. Just regular talking, like ‘Hey, this happened at work today. It was so-and-so’s birthday.’ You want to be as normal as you can. The reality is that life goes on.”

Terry Stanton is the former senior medical writer for AAOS Now.