I have been serving in short-term missions in the developing world since 2003—especially in Africa. So, I had the preconceived notion that I was completely accustomed to that environment and that I was more or less immune to the inevitable culture shock. My most recent trip to CEML Hospital (Centro Evangélico de Medicina do Lubango) in Lubango, Angola, over the Thanksgiving 2024 holiday shattered that presumption.

In March 2024, I ran into Annelise Olson, MD, a general surgeon working as a medical missionary in Angola since 2011. Dr. Olson is formally trained in general surgery in the United States, but she has spent her entire career as a surgeon in Africa doing abdominal, neurosurgical, obstetric, gynecologic, plastic, and orthopaedic surgery. I was teaching orthopaedic surgery in the basic science course for the Pan-African Academy of Christian Surgeons in Limuru, Kenya. Dr. Olson reminded me that 10 years earlier, I had promised her that I was going to visit Angola and teach her and her partner how to do total hip replacements. I never went, and so she found someone else to teach them. She then proceeded to guilt me into coming to teach them total knee arthroplasty (TKA).

Unfortunately, I am an orthopaedic trauma surgeon who hasn’t done a total knee in 15 or more years. Fortunately, one of my postgraduate year 4 (PGY-4) residents, Michael DeRogatis, MD, who has a passion for total joint arthroplasty and was in the match for an adult reconstructive fellowship, wanted to go to Angola with me. Off we went!

Working in the developing world can be extremely challenging. Vaccinations for yellow fever and typhoid and prophylaxis for malaria are things that most North American surgeons have not experienced. Many places that really need our help are difficult to access. Although much of Africa speaks English, Angola is a communist country that speaks Portuguese. Add in the paucity of surgical implants, minimal technology, severe pathology, and a general sense of culture shock, and you have a good picture of what awaited us.

Having been in similar settings many times, I was quite accustomed to much of what I encountered. For some reason, this time, whether it is my stage in life or something else, the degrees of suffering and poverty struck me harder than they had in a very long time. Several facts were very clear. The Angolan patients were in the “infinite game”—an idea from Simon Sinek’s book of the same title. The infinite game refers to people adopting a more wholesome view of life by not keeping score of who “wins” and who “loses” in daily life. There is much to this concept, and I would encourage readers to review Sinek’s book. These patients displayed a general sense of contentment and joy amidst severe struggle, poverty, and need. Secondly, I clearly saw patients who would tremendously benefit from whatever care I could provide regardless of the implants and technology I was accustomed to using. Lastly, the existential crisis I encountered there rocked my general sense of stability and personal meaning more than ever before. Though I have been in the developing world many times, the tremendous chasm between my normal life and this life that was calling me there overwhelmed my sense of purpose.

Teaching U.S.-trained general surgeons to perform TKA is unusual in its own right. Unlike North America, general surgeons in these environments care for the “skin and its contents.” They routinely treat urologic, gynecologic, neurosurgical, oncologic, and orthopaedic conditions. In fact, more than half of the patients treated at the CEML Hospital in Lubango presented with an orthopaedic complaint. Pott’s disease and tuberculous arthritis are extremely prevalent.

The complexity of orthopaedic complaints surpassed most of what I treat in my Pennsylvania trauma practice. The patients with degenerative arthritis of the knee had severe deformity in addition to advanced arthritis. Patients presented with fracture dislocations of the ankle that were months old. Many fractures were either healed with a significant deformity or presented as a chronically infected nonunion. Unrecognized and untreated sarcomas were so advanced that palliative care was the only possible treatment. A patient with an unstable pelvic ring injury with a 10-centimeter diastasis of the pubic symphysis left the first hospital and came to CEML begging for help with no idea that an American orthopaedic trauma surgeon happened to be there!

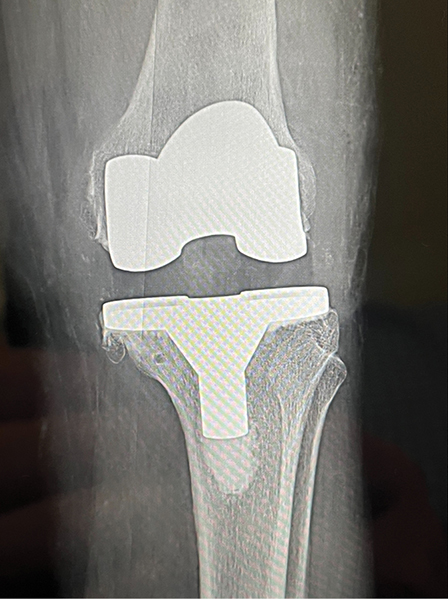

With orthopaedic pathologies like these, why teach general surgeons to do TKAs? In a culture highly reliant on walking, functioning hips and knees are critically important. Advanced arthritis and severe deformity significantly impact patients’ lives and livelihoods, making simple activities incredibly difficult. Survival for many people in these communities requires them to walk miles daily to obtain water and food. The missionary surgeons had secured a basic system of posterior stabilized total knee components and instruments, so we decided to see whether this procedure would be a viable option in that setting.

With patients who clearly met the indications, we assessed the operative environment. Although different from North American ORs, the surgical capacity in CEML had what we needed. The Angolan teams were completely engaged. We strongly emphasized the need for sterility and thorough postoperative care. So, after a deep breath, Dr. DeRogatis, my PGY-4 resident, led me and the missionary surgeons through our first West African TKA, clearing the cobwebs off my TKA skills!

Over the course of a week, we performed eight TKAs in addition to multiple fracture reconstructive cases, including the patient with the unstable pubic diastasis. With only one set of total knee instruments, we could only do two arthroplasty cases per day. Our general surgery hosts learned the procedure incredibly fast, and before long they were doing the cases “skin to skin.” Their understanding of flexion/extension gap, soft-tissue balancing, and component positioning was astonishing to this middle-aged trauma surgeon who believed that only orthopaedic surgeons were capable of this kind of work.

I strongly encourage readers to consider exploring opportunities like these. Many friends have told me that they want to do foreign mission work, but they want to wait for the “right time.” The problem is that the right time almost never comes. Keep a very open mind, remembering that the principles of orthopaedic surgery work throughout the world regardless of the circumstances. Humility goes a long way in these situations, recognizing that local surgeons are doing the best that they can with the resources they have available. Almost always, visiting surgeons learn and take away more than they left behind. Lastly, be aware that these experiences can reignite your passion for orthopaedic surgery and have the potential to change your life.

Douglas W. Lundy, MD, MBA, FAAOS, is chair of orthopaedic surgery and chief of orthopaedic trauma surgery at St. Luke’s University Health Network. Dr. Lundy is a member of the AAOS Now Editorial Board.

- Sinek SO. The Infinite Game. New York: Portfolio Publishing; 2019.