Editor’s note: This article is the second in a two-part series on important knowledge deficits facing physicians new to practice. Part one, which discussed the challenges of surgeon turnover and the importance of successful onboarding, was published in the January issue of AAOS Now.

For orthopaedic practices hiring new surgeons, onboarding begins after recruiting the new hire and ensuring there is a mutual “good fit” with the workplace. The onboarding program starts with signing the employment contract and should not be considered complete until at least the end of the first year of practice. Although each organization is different and has different needs, there are a few key steps that practices can take to conduct successful onboarding.

An effective onboarding program emphasizes to new hires that the practice is invested in their success. Programs should generally include clear goals and expectations, selection of a mentor, training, assistance with socialization, success measures, and an ongoing improvement process. The onboarding process should proceed in a well-defined and structured fashion that includes several phases: planning, welcoming, training, and transition and integration (see the Sidebar for a breakdown of each phase).

Phase 1: planning

The planning phase should take place 4 to 6 months prior to the new hire’s start date. Once a recruited physician accepts an offer, the planning, or pre-onboarding, process can begin.

Licensing and credentialing can take an extended period, especially state licensing, so this process should start immediately. Make license applications an early onboarding priority, to ensure the physician can see patients and bill for services on day one. It is vital to engage the new physician-recruit to be an active, responsive, and timely part of the complex licensing process.

Additionally, institutional culture, history, strategy, and vision should all be shared with the new hire. An assigned mentor can be a vital part of this stage. The department or group should establish a mentoring program with volunteers who are willing to commit the time necessary with the new physician. Although this may affect productivity, the payback for the group and the individual new hire is immense. Consistent messaging by the group will ensure that new hires understand expectations and their roles.

Phase 2: welcoming

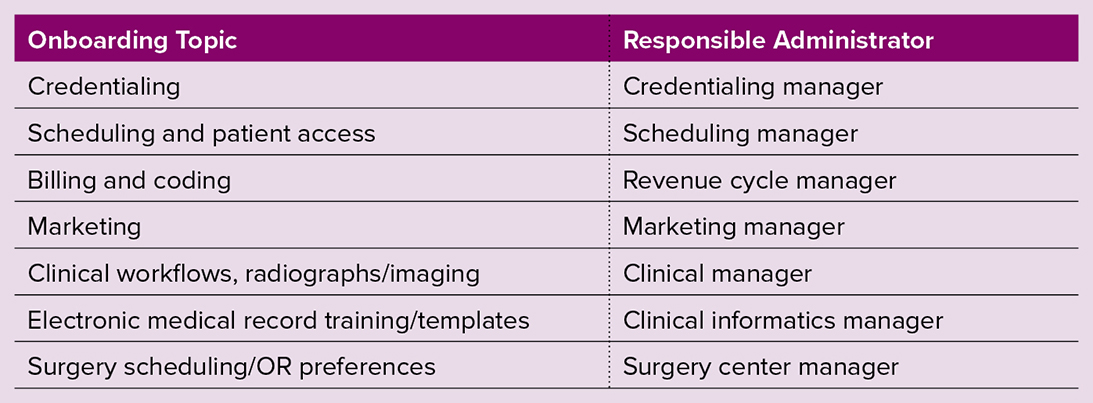

The welcoming phase includes making an announcement and introductions to relevant parties, including department/division chiefs, relevant clinical personnel, and referring physicians (Table 1). Prioritize meet-and-greets and clinical talks with primary care and other referring physicians and the community. Initially, these foundational activities are more important than clinical productivity, and the new surgeon should be educated on this new skill set and reassured that practice development should be their priority.

External marketing to advertise the new surgeon’s arrival and expertise should be carefully planned and executed over the first few months and throughout their first 1 to 2 years in practice. Marketing should continue as they develop their practice.

It is common for many new graduates to leave fellowship at the end of July and use the month of August as a transition month. A low-stress, spread-out transition to practice can be completed during this time, consistent with a process described by Etheridge et al as the “four Cs”: compliance, clarification, culture, and connection. It is imperative to start professional mentoring during this phase and continue it throughout onboarding.

Phase 3: training

The training phase is the most important and longest part of onboarding. Care should be taken to avoid overwhelming the new physician. Emphasize responsibilities and expectations, and tailor this phase for the new hire according to their experience and expected role. Thoughtfully design electronic medical records, dictation systems, and coding and billing training so that the surgeon is trained in how to complete their tasks by a specified timeframe. Complete chart review and coding and billing review as well as analysis of patient outcome metrics on a regular basis, providing quick, actionable feedback. Frequent updates ensure that early habits can be reinforced or supported. Where possible, it can be invaluable to provide shared clinic space for the new physician to observe and model behavior and efficient processes from mentors.

As new and early-career physicians may not yet have been in significant leadership positions in their careers, they should receive support and training on how to effectively lead their team and set expectations with clinical and OR staff. Often, workshops and seminars can be created as online modules, which can be assigned for completion within a specified timeframe and done on the new hire’s preferred schedule.

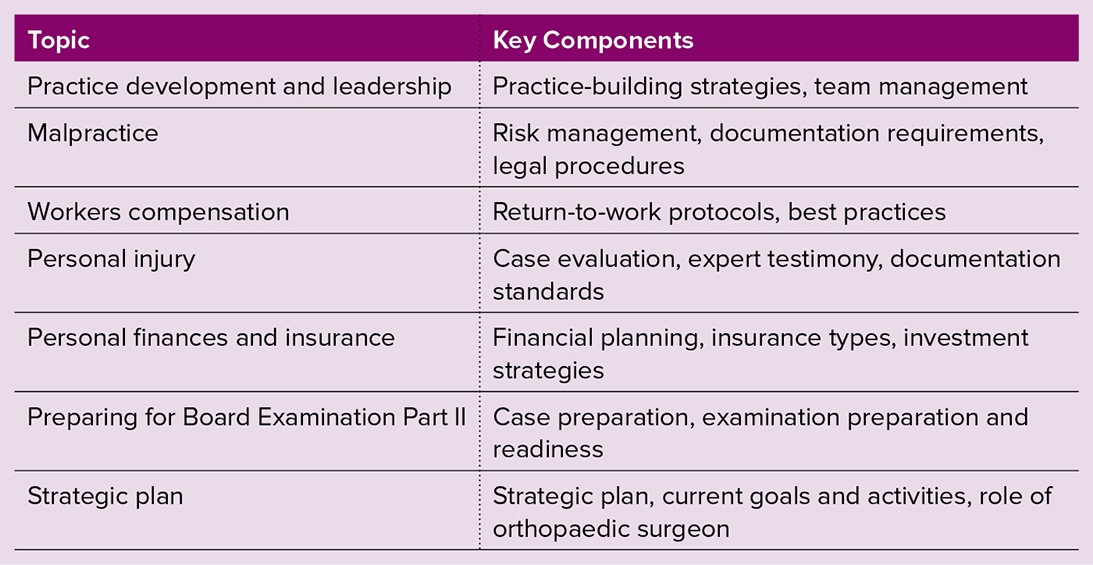

For larger topics that are of benefit to all new hires, an onboarding curriculum including a dinner lecture series can be efficient and serve as a bonding event, especially in the case of multiple new hires. Topics for these sessions vary among organizations but can include a wide variety, listed in Table 2.

Phase 4: transition and integration

The transition and integration phase is the final part of the onboarding process, as the new physician becomes established and their role evolves and deepens. This phase emphasizes committee work and continuous practice monitoring and quality improvement. As the physician’s practice matures, locations for clinic and/or surgery may require modification depending on volume changes. Earlier parts of the onboarding process may need to be revisited to ensure understanding.

Academic onboarding

Academic onboarding is similar to clinical practice, with additional training in the role of academic promotion. The criteria for promotion, influence on salary, and evaluation criteria must be thoroughly explained and understood. For faculty who are passionate about research, coaching on how to allocate research time, collaborations, and grant funding is critical. Institutional priorities, capabilities, and resources will enable the new physician to develop a successful strategy. Multilayered onboarding with scientific mentorship aligning with research goals and interests is critical to onboarding success.

Conclusions

Effective onboarding will increase new physician satisfaction and result in improved physician retention and ultimately improved patient satisfaction. At a time of increasing patient demand due to an aging population and accelerating surgeon retirement, the retention of orthopaedic surgeons is critical to practice success.

In addition, for those institutions where academic achievement is imperative, each surgeon’s academic journey needs guidance as well. The process involves multiple steps over a year-long period to effectively incorporate new physicians into the culture of the practice. A systematic program incorporating both administrative staff and current physicians is critical to success.

Brandon W. King, MD, FAAOS, is a clinical assistant professor at Wayne State University School of Medicine, a clinical assistant professor at Michigan State University College of Human Medicine, and an orthopaedic surgeon at Henry Ford Health in Detroit.

Erika A. Noll is chief operating officer at Peachtree Orthopedics in Atlanta.

Jonathan P. Braman, MD, MHA, FAAOS, is chair of orthopaedic surgery and medical director of the orthopaedic service line at Henry Ford Health in Detroit.

Xavier A. Duralde, MD, FAAOS, is an emeritus physician at Peachtree Orthopedics in Atlanta.

References

- Stajduhar T: The High Costs of Hiring the Wrong Physician. Available at: https://www.nejmcareercenter.org/minisites/rpt/the-high-costs-of-hiring-the-wrong-physician/. Accessed Jan. 3, 2024.

- Etheridge JC, Goldstone RN, Harrington B, et al: Implementation of a new surgeon onboarding program in an academic-affiliated community hospital. Ann Surg 2023;278(6):e1156-8.

- Cogbill TH, Shapiro SB: Transition from training to surgical practice. Surg Clin North Am 2016;96(1):25-33.

Components of each phase of orthopaedic surgeon onboarding

Phase 1: planning

- licensing and credentialing process

- Drug Enforcement Agency, Medicare, and malpractice numbers

- hospital/ambulatory surgery center privileges

- orientation to group/community culture

- allocation of office and clinic space

- mentor assignment

- meeting with administrative leaders (see Table 1)

- human resources, employee benefits, billing, clinical

- marketing

- photos, bio, website additions

- social media presence

Phase 2: welcoming

- the four Cs: compliance, clarification, culture, and connection

- announcements to staff and community

- introductions to emergency department and OR personnel

- introductions to primary care referrals

- introductions to department/division chiefs

- social media marketing

- ordering of apparel

- electronic health record training

- completion of processes started in phase 1 (e.g., credentialing)

- mentoring by colleague

Phase 3: training

- expectations and training on task completion

- charting, coding, billing, dictation, personnel policies

- team leadership training

- practice contact numbers

- holiday schedules

- clinic and OR block scheduling

- on-call schedules

- onboarding curriculum (see Table 2)

Phase 4: transition and integration

- introduction to committee work

- performance feedback metrics

- block utilization, clinic volume, patient outcomes and satisfaction

- schedule adjustment based on volume

- clinic and OR

Considerations for academic onboarding

- discussion of academic promotion

- expectations/criteria for promotion (e.g., research, teaching, committee service)

- grant funding

- introduction to lab personnel

- mentoring (clinical and scientific)