A study evaluating the efficacy of a custom 3D-printed total ankle total talus replacement (TATR) prosthesis in patients with failed total ankle replacement (TAR) found that this custom revision option demonstrated significant improvements in patient-reported outcomes and that all implants remained intact at final follow-up.

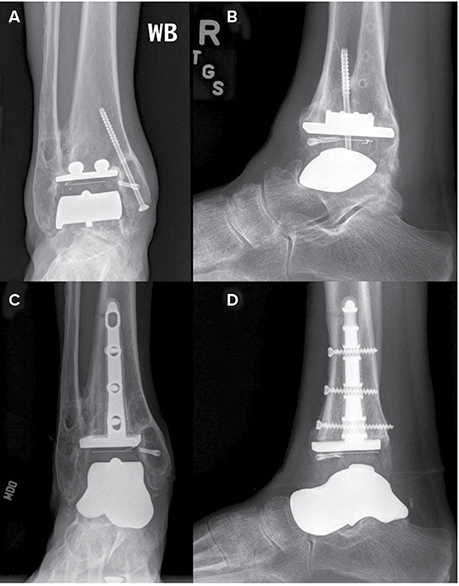

The study was presented at the AAOS 2024 Annual meeting by Jonathan Day, MD, orthopaedic resident at Georgetown University Medical Center. The final analysis involved 19 patients (10 female) available for 2-year follow-up, among 45 participants initially identified who underwent revision TATR (Fig. 1) in the setting of failed TAR with aseptic loosening or subsidence and/or talar avascular necrosis. Included patients had follow-up radiographs and preoperative and/or postoperative Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) data responses.

Mean follow-up was 37.9 months (range, 25.3–57.5). The indications for custom TATR included aseptic loosening (n = 9), avascular necrosis of talus (n = 10), implant subsidence (n = 3), infection (n = 2), and others (n = 1). Preoperative PROMIS surveys were completed by 14 participants (seven female), and both pre- and postoperative PROMIS surveys were completed by 12 participants (six female). Radiographic outcomes were obtained in all participants. Eight procedures were right-sided, and 11 were left-sided. The average age was 60.6 years (range, 39–77), and the average BMI was 30.1. The average time to failure after primary TAR was 50.9 months (range, 6.4–113.2).

At final follow-up, all custom implants were intact, without evidence of hardware failure or implant subsidence. Comparison of pre- and postoperative PROMIS data showed statistically significant improvement across all study domains. The average preoperative physical function score improved by 8.8 points from 37.2 (± 2.3) to 46.0 (± 2.3) (P <0.05). pain interference scores decreased by 14.8 points (63.9 ± 2.3 to 49.1 ± 3.0) (>P <0.01), and pain intensity decreased by 11.9 points from 55.3 (± 3.0) to 43.4 (± 3.4) (>P <0.01). global physical and mental health both significantly improved as well. global physical health scores increased by 8.9 points from 41.0 (± 6.1) to 49.9 (± 6.1) (>P <0.05), and global mental health scores increased by 4.5 points from 54.4 (± 4.8) to 58.9 (± 5.2) (>P <0.05). depression scores dropped by 10.3 points from 52.7 (± 2.8) to 42.4 (± 3.6) (>P <0.05).

The average postoperative radiographic follow-up timeframe was 16.5 months (range, 4.3–54.9 months). There were no statistically significant differences in pre- to postoperative radiographic coronal or sagittal alignment in terms of medial distal tibial angle (89.9 versus 86.4 degrees), tibiotalar angle (89.7 versus 88.1 degrees), or sagittal tibial angle (85.2 versus 85.3 degrees).

Two participants (11 percent) had postoperative complications; one participant underwent open reduction and internal fixation of the tibia for a tibial periprosthetic fracture 1 month postoperatively (Fig. 2), and another participant underwent medial gutter debridement and tarsal tunnel release for recurrent pain 14 months postoperatively.

The authors commented that failed total ankle arthroplasties “pose significant challenges, representing a patient population with substantial unmet needs” and that “naturally, revisions are more challenging given the need for explanation as well as addressing bone loss, infection, and/or malalignment.”

“With many modern implants now available on the market, there is an increasing focus on optimizing patient outcomes through advancements, including patient-specific instrumentation and revision options,” Dr. Day said. “It is an exciting time to be involved in this research. At our tertiary academic hospital, we see many complex patients from all walks of life. Some of these patients have had previous TAR which require revision. When this is combined with poor bone stock and/or talar avascular necrosis, the revision options are limited. Therefore, we were interested in evaluating the efficacy of custom 3D-printed TATR in this unique subset of patients.”

Dr. Day said he and his colleagues “were pleased to find that this custom revision option demonstrated significant improvements in patient-reported outcomes and that all implants remained intact at final follow-up.” He also noted they were surprised to find no significant differences in radiographic alignment postoperatively but added, “This may have also been due to the lack of significant preoperative malalignment.”

He said the next steps of investigation should be aimed at determining which patients would be most suitable for the TATR procedure and, conversely, whether there are any risk factors that predict a poor outcome. Limitations of the study included the relatively small case series and the unique subset of patients, Dr. Day said.

“We hope that this study presents a viable solution to a clinical problem and stimulates new ideas and collaboration within the orthopaedic community to further advance our understanding of treatment for end-stage ankle osteoarthritis,” he said.

Dr. Day’s coauthors of “Early Efficacy of Combined Total Ankle Total Talus Replacement in the Revision Setting” are Joyce En-Hua Wang, BA; Julia McCann, MD; and Paul Cooper, MD.