The Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence, Italy, is home to Michelangelo’s famed statue of David. A masterpiece to many, the colossal statue has humble beginnings, starting as a block of marble that was left untouched outside for more than 30 years. Multiple artists were consulted to work on this marble, including Leonardo da Vinci, but none was willing to undertake the difficult task. It was not until August 16, 1501, that 26-year-old Michelangelo was commissioned for the piece for the Florence Cathedral.

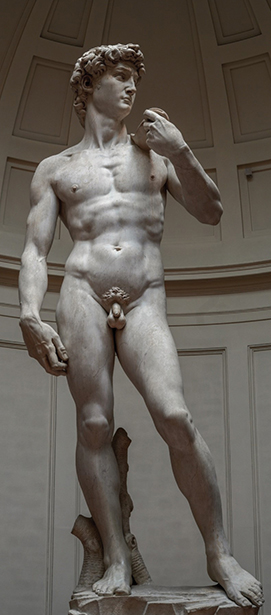

This great work would take him more than 2 years to complete. The result is a 17-foot-tall statue of the biblical figure David, considered to be one of the world’s greatest works of art (Fig. 1). Originally intended to line the buttress of the Florence Cathedral, the statue of David was instead placed in the town square for all to see.

As a creation made during the High Renaissance, the statue of David was expected to be perfect. Michelangelo sculpted meticulously with a precise attention to detail, courtesy of the anatomical training he underwent. Muscles, such as the sternocleidomastoid and abductor digiti minimi, and bulging veins are present throughout the statue in their proper locations. At the same time, Michelangelo accounted for the perspective of viewers looking up at the statue by sculpting certain body parts to be disproportionate to others. Some also believe that these atypical proportions were added to emphasize certain traits, such as David’s larger right hand, which may have been a reference to a nickname for David in the Middle Ages—“manu fortis,” meaning “strong of hand.” Regardless, it is clear that the disproportions were incorporated by design, considering Michelangelo’s precise approach to anatomy.

The statue’s artistic brilliance is without debate, though there is one glaring imperfection—particularly to shoulder surgeons. When viewed from behind, the right infraspinatus muscle is missing from David’s scapula (Fig. 2). There is no evidence that the biblical David had such a shoulder diagnosis or if 16th-century caregivers appreciated infraspinatus atrophy. Michelangelo seems to be aware of this defect because, in one of his letters, he wrote that there was a defect in the block of marble that prohibited him from reproducing the muscle.

Yet within imperfection lies perfection. Despite not having modern-day knowledge, Michelangelo may have incidentally recreated a common shoulder deformity. The movements of a throwing athlete place the arm in an abducted and externally rotated position. Repetition of this movement over time leads to strain on the biceps tendon and a gradual tearing of the posterosuperior labrum from the glenoid. This can result in a superior labral anterior to posterior (SLAP) lesion. This labral defect creates a one-way valve in which fluid collects outside of the joint. This forms what is known as a spinoglenoid cyst. It is well documented in modern literature that spinoglenoid cysts have an incidence of nearly 90 percent with a concurrent SLAP lesion. As the cyst continues to grow, compression occurs on nearby structures, including the suprascapular nerve. Over time, denervation of the infraspinatus muscle leads to atrophy. Surprisingly, the muscle that is missing on the statue of David perfectly correlates with infraspinatus atrophy secondary to a SLAP lesion (Fig. 3). This is a common condition found in a throwing athlete, such as a baseball pitcher or an ancient sling wielder.

According to Michelangelo, the missing muscle was a defect in the marble; however, the statue of David presents another oddity that questions this statement. The statue holds the sling in its left hand, suggesting that David is a left-handed thrower—but the statue is standing in a right-handed thrower’s position. For an artist as precise as Michelangelo, how did this mistake occur? Or is it even a mistake at all? In fact, athletes with SLAP lesions, especially when untreated, are forced to adapt to compensate for their injury. In the case of a sling thrower, this would entail learning to throw with the non-dominant arm.

There are a few possible explanations for how Michelangelo incorporated this unique finding into his sculpture. The model who Michelangelo based the sculpture on may have been an athlete with a SLAP lesion and concomitant suprascapular nerve injury. This would explain why the statue of David is in a contradictory position, as the model would be doing such. However, there is a possibility that Michelangelo worked alone on this sculpture. In that case, the contradiction in sling placement and throwing stance may be related to the fact that SLAP tears were most likely undiagnosed and untreated in the 1500s. The first SLAP tear was not described until 1985 by James Andrews, MD. Studies report a prevalence for SLAP tears to be around 3.9 to 6 percent in patients undergoing shoulder arthroscopy, but the true prevalence may be even higher—particularly in Michelangelo’s time, considering recent advancements in modern medicine. As a result, Michelangelo may have incidentally sculpted a SLAP tear because it was a more common occurrence at the time.

Explanations for the reason behind the statue of David’s missing muscle have been difficult to determine through historical texts. However, what may have been an imperfection back in the 1500s is proving to be a perfect replication of a more well-known pathology. The statue of David, with its beauty, scale, and history, continues to awe spectators to this day, cementing its legacy as a masterpiece beyond compare, yet still holding surprises of its own.

Andrew Ko, BS, is a previous research fellow at the Hughston Foundation and a current medical student at the Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell.

Brent Ponce, MD, is an orthopaedic surgeon at the Hughston Clinic and chairman of research at the Hughston Foundation in Columbus, Georgia.

Patrick Fernicola, MD, is an orthopaedic surgeon at the Hughston Clinic in Columbus, Georgia. This article was prompted from his most recent vacation to Florence.

References

- Popovic A: Evolution of art history presentation of strength and human body through the example of David. Conference Proceedings of the 18th International Session on Olympic Studies for Postgraduate Students Proceedings. International Olympic Academy. Sept. 2011;97–106. Athens, Greece.

- Cummins CA, Messer TM, Schafer MF: Infraspinatus muscle atrophy in professional baseball players. Am J Sports Med 2004;32(1):116-20.

- Nan Palmero. David (Michelangelo). Flickr. www.flickr.com/photos/nanpalmero/51351265446/. Published July 20, 2021. Accessed Sept. 3, 2023.

- Summers D: Contrapposto: style and meaning in renaissance art. The Art Bulletin 1977 59(3):336-61.

- Buonarroti M: Le lettere di Michelangelo Buonarroti pubblicati coi ricordi ed i contratti artistici. Florence: Claudio Paganelli, 1875:620-3.

- Gelfman DM: The David sign. JAMA Cardiol 2020;5(2):124-5.

- Gomez DN, Zulkahini NF, Ahmad AR, et al: Isolated infraspinatous atrophy from a spinoglenoid cyst: a case report. Malays Orthop J 2022;16(1):142-5.

- Levine S: The location of Michelangelo’s David: the meeting of January 25, 1504. The Art Bulletin 1974;56(1):31-49.

- Parks NR: The placement of Michelangelo’s David: a review of the documents. The Art Bulletin 1975;57(4):560-70.

- Pazhoohi F, Macedo AF, Doyle JF, et al: Waist-to-hip ratio as supernormal stimuli: effect of contrapposto pose and viewing angle. Arch Sex Behav 2020;49(3):837-47.

- Piatt BE, Hawkins RJ, Fritz RC, et al: Clinical evaluation and treatment of spinoglenoid notch ganglion cysts. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2002;11(6):600-4.

- Popp D, Schöffl V: Superior labral anterior posterior lesions of the shoulder: current diagnostic and therapeutic standards. World J Orthop. 2015;6(9):660-71.

- Shaikh S, Leonard-Amodeo J: The deviating eyes of Michelangelo’s David. J R Soc Med 2005;98(2):75-6.

- Shaked G: Secrets of Italian Sculpture. Lulu.com; 2010.

- Steinberg L: Michelangelo’s Painting: Selected Essays. University of Chicago Press; 2019.

- Varacallo M, Tapscott DC, Mair SD: Superior Labrum anterior posterior lesions. Available at: https://www.statpearls.com/point-of-care/29703. Accessed Sept. 3, 2023.

- Mohana-Borges AV, Chung CB, Resnick D: Superior labral anteroposterior tear: classification and diagnosis on MRI and MR arthrography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003;181(6):1449-62.

- Buonarroti M: David. Rear View. Available at: https://arthive.com/michelangelo/works/209426~David_Rear_view. Accessed Sept. 3, 2023.

- Abbasi D: Suprascapular Neuropathy. Available at: https://www.orthobullets.com/shoulder-and-elbow/3063/suprascapular-neuropathy. Accessed Sept. 3, 2023.