Editor’s note: The Final Cut is a recurring editorial series written by a member of the AAOS Now Editorial Board.

Long gone are the days of the small-town doctor, the generalist who makes house calls with a black bag and accepts payment in the form of baked goods and fresh eggs. This Norman Rockwell–esque view of medicine has been supplanted by specialization and subspecialization, where every organ and body part seem to have their own set of experts. As medical knowledge and technology have expanded, so has the potential quality of healthcare provided, which I believe has been a positive for the U.S. healthcare system. Orthopaedic surgery is no exception, with many subspecialty areas. However, orthopaedics is a field in which I believe it is still necessary for a subset of surgeons to remain generalists.

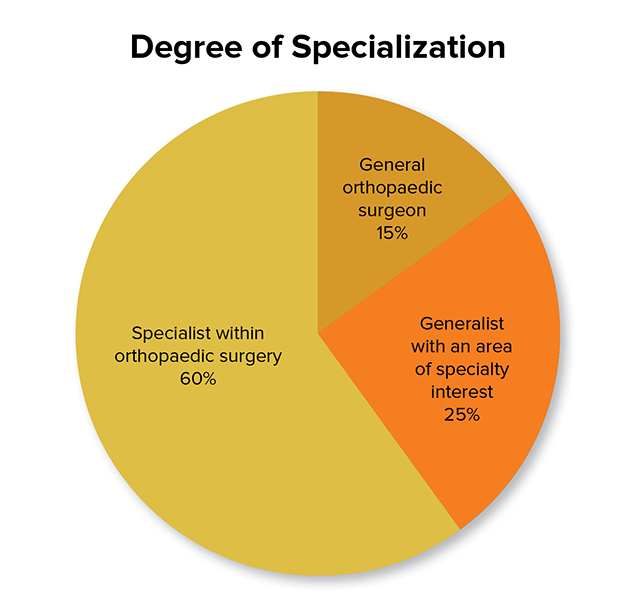

Are orthopaedic generalists a dying breed? According to the 2018 AAOS Orthopaedic Surgeon Census, 60 percent of orthopaedic surgeons are specialists (Fig. 1). Twenty-five percent define themselves as generalists with a specialty interest, and only 15 percent are generalists. Compared with the 2008 census, there has been an increase in the number of surgeons who call themselves specialists and a decrease in generalists. Furthermore, specialists tend to be younger surgeons with fellowship training, whereas generalists tend to be older. As these surgeons continue to age and eventually retire, it stands to reason that generalists’ numbers will continue to dwindle without young surgeons choosing this practice style.

I am a generalist. I hail from a tiny town of 1,000 people in western Kentucky, where getting our second stoplight was front-page news. Training took me to several large cities, but I still chose to come back to Kentucky. It’s no secret that Kentucky has a fair number of socioeconomic challenges, but I feel like I can make a difference here. (Not to mention the nature is gorgeous if you’re outdoorsy like I am.)

Compared with a national poverty rate of 11.5 percent, Kentucky sits around 16.5 percent, with one-third of the population on Medicaid. I am one of four orthopaedic surgeons working at a 300-bed regional hospital with a service area of 165,000 people; roughly 40 percent of those patients are on some version of Medicaid. The adjacent county was recently deemed the poorest county in the United States. State unemployment is 4.3 percent, but in some counties it reaches 11 percent or higher, and the minimum wage is $7.25 per hour.

Additionally, though the people here are some of the best, biggest-hearted people you’ll meet, they often are not the healthiest. We rank No. 1 in the United States in death from cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, No. 2 for death from sepsis, and No. 3 for death due to accidents, according to 2017 data. There is a lot of work for doctors here. But difficulty accessing healthcare is very real for many patients. Lack of public transportation or money for a vehicle and fuel is a barrier. People can barely afford to make it to my office, much less the 90 minutes to the nearest big “city” with a level 1 academic trauma center. This socioeconomic snapshot is not unique to Kentucky; it exists in many regions across the United States.

When people need or want to stay local, it’s really nice to be able to help them. I love that I can see patients of all ages with a wide variety of pathologies. In recent months, my youngest patient was an infant; the oldest, 93 years. I’ve had patients with trauma, some with severe infections, and I have been the first to diagnose cancer via metastatic lesions. I’ve placed wound vacs and many, many casts.

As a generalist, I get to do a lot of different things in the OR as well. In the past 6 weeks, I’ve treated hip fractures; done elective hip/knee arthroplasty; repaired rotator cuffs and torn menisci; treated a variety of fractures (fingers, forearm/wrist, femur, ankle, tibia); done cubital/carpal tunnel releases; and performed fasciotomies, amputations, and skin grafts.

Performing this wide variety of procedures challenges me as a physician to deepen my knowledge base and skill set. I’ve treated entire families, spouses experiencing broken hips months apart, and parents and their children. I’ve become a musculoskeletal primary care physician of sorts, and although I never saw myself in that role, I’ve come to love it.

In rural areas with lack of access to care, high levels of poverty, often poor education, and distrust in the medical establishment, I love that I can provide care to everyone. I can establish trust and get to know my patients on a deeper level than I feel I could in a subspecialty area. With time, I believe practices such as mine can help improve the health of the community and help bridge the gap in situations where access to larger systems and subspecialists is difficult. Even when access is possible, wait times have turned into months as systems become overwhelmed.

I care deeply about my community and my state (go Big Blue!) and feel like I’m fulfilling my calling as a surgeon by practicing as a generalist. For someone who loves variety and performing multiple types of surgeries, a generalist practice satisfies the itch to do new things and combats the fear of becoming bored. It doesn’t get much better than that. My hope is that as more surgeons come out of training and find that markets in larger cities are saturated, they realize when they settle in more rural areas that a generalist practice is not only a necessity but a wonderful way to practice. Hopefully we will no longer be a dying breed, but a specialty that will flourish.

Leslie Schwindel, MD, FAAOS, is a general orthopaedic surgeon at Lake Cumberland Regional Hospital in Somerset, Kentucky.

References

- AAOS: Orthopaedic Practice in the U.S. 2018. Available at: https://www.aaos.org/quality/practice-management/aaos-orthopaedic-surgeon-census/orthopaedic-practice-in-the-u.s.-2018. Accessed Dec. 4, 2023.

- United States Census: QuickFacts: Kentucky. Available at: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/KY/POP060210. Accessed Dec. 4, 2023.

- Stebbins S: Poorest counties in the US: A state-by-state look at where median household income is low. Available at: https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/2019/01/25/poorest-counties-in-the-us-median-household-income/38870175. Accessed Dec. 4, 2023.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Stats of the State of Kentucky. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/states/kentucky/kentucky.htm. Accessed Dec. 4, 2023.