Cement-in-Cement Revision Arthroplasty Technique

Introduction

Cement-in-cement revision arthroplasty may be considered for aseptic loosening at the prosthesis-cement interface, to change the stem position (length, version, or offset), or if stem removal is necessary to improve access for revision of the acetabular component. Advantages of cement-in-cement revision arthroplasty over other types of revision include preservation of bone stock and shorter surgical time. The cement-bone interface must be well preserved, and any loose cement must be removed. Relative contraindications to cement-in-cement revision arthroplasty include a cement-bone interface disruption of more than 2 cm and/or including the lesser trochanter. Reported outcomes of cement-in-cement revision arthroplasty range from 82% implant survival at a follow-up of 6 years to 96% implant survival at a follow-up of 11 years, with good midterm patient-reported outcomes. Cement-in-cement revision arthroplasty is mainly performed in patients without known infection, and limited published data shows mixed results. This video describes the surgical technique for cement-in-cement revision arthroplasty of the femoral component used at our institution.

Materials and Methods

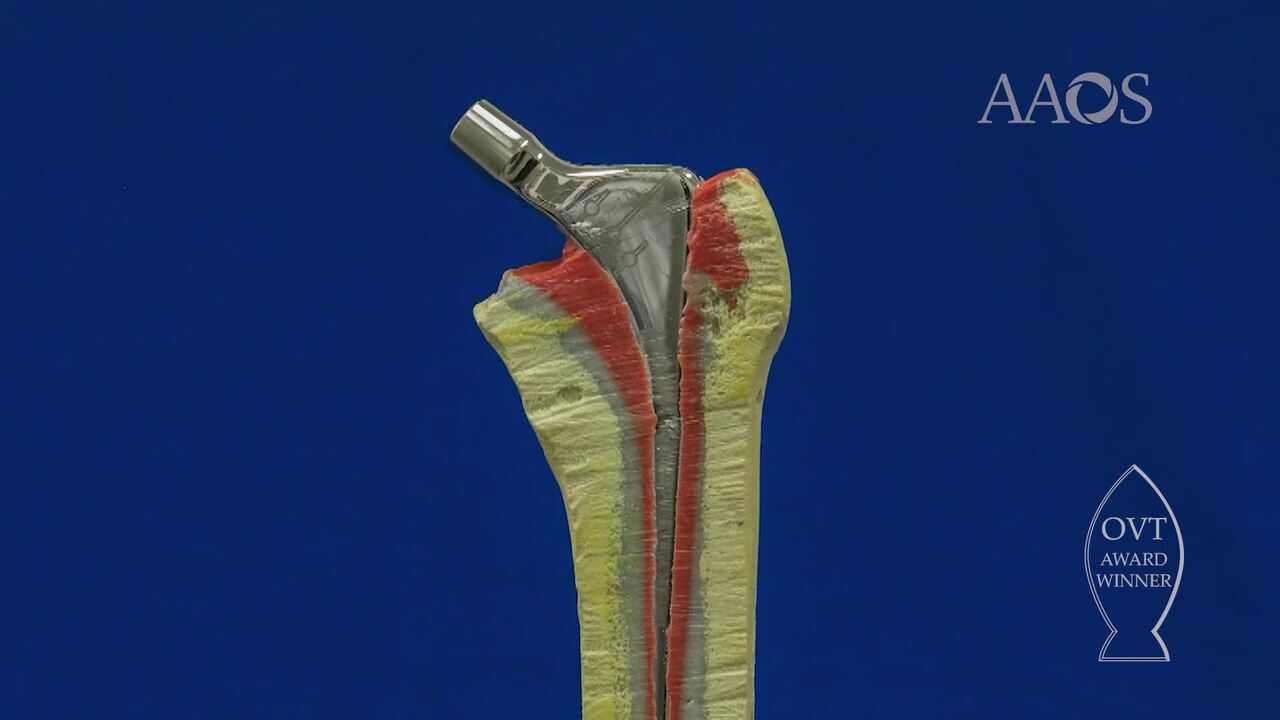

The video discusses the case presentation of a 61-year-old man with a chronically dislocated hemiarthroplasty implant that is lacking in offset and has extensive cementation down the canal. After exposure and dislocation, all tissue overhanging the stem shoulder and bone-cement interface was removed. The implant was removed, and a cerclage wire was placed prophylactically around the proximal femur to prevent fracture. The remaining cement mantle was burred, and the surface was roughened to improve cement-to-cement bonding. All loose proximal cement was removed, and the canal was washed thoroughly. The cement mantle and the bone-cement interface were inspected for defects. Trial implants were used to assess limb length, offset, stability, and impingement, and the desired level of the stem shoulder was marked on the greater trochanter. The trial stem was removed, and the canal was dried to allow for a good cement-to-cement bond. Cementation was performed using a narrow nozzle cut to the appropriate length for the implant, and the stem was inserted while the cement was still runny.

Results

Full-weight bearing was permitted immediately postoperatively. Postoperative radiographs for this patient demonstrated a good cement mantle and restoration of offset. The initial results of 23 patients who underwent cement-in-cement revision arthroplasty of the femoral component at our institution were published in 2007. No intraoperative complications were reported, and 19 patients had no re-revision procedures or radiographic evidence of failure at a median follow-up of 5 years. Recent results in 65 patients, including 10 patients with large proximal cement mantle defects contained via mesh and bone graft, revealed similar stem survival in patients with defects and patients without defects. No revision procedures for aseptic loosening occurred during the 18-year study period, and overall stem survival was 90% at a mean follow-up of 7 years (range, 2 to 18 years). Postoperative Harris hip pain scores at all time points had improved compared with preoperative Harris hip pain scores.

Conclusion

Cement-in-cement revision of the femoral stem may reduce surgical time and complications in appropriately selected patients while providing acceptable midterm to long-term results.